Emerging defence businesses frustrated with local innovation ecosystem

A strong, end-to-end system that fosters innovation is essential to support emerging businesses in Australia’s defence sector. This is the view of QuantX Labs’ managing director and co-founder, Professor Andre Luiten.

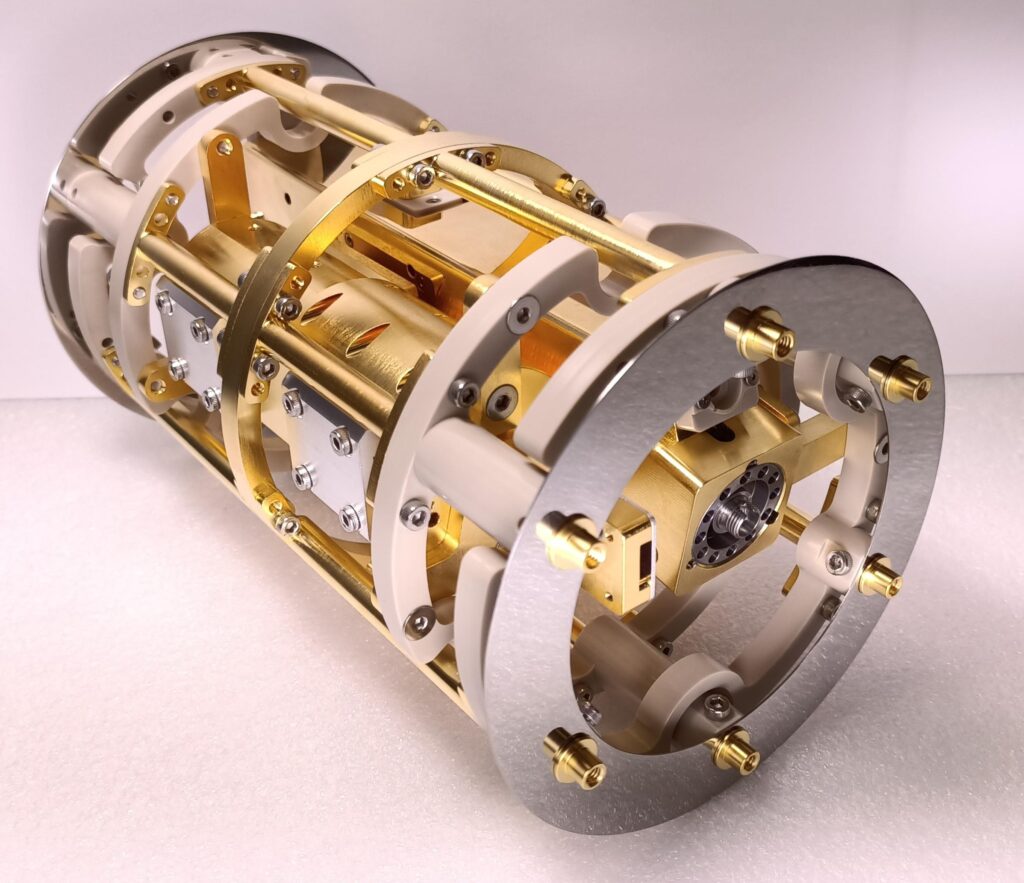

The business is developing a suite of precision timing and quantum sensor products for communications, navigation, surveillance and defence systems.

With its partner BAE Systems, QuantX Labs has developed technology that allows radars to see small objects with greater clarity. Another product allows users to detect objects through oceans and the ground, making the water and earth invisible to see what’s happening through them.

QuantX Labs is assisting the Australian Defence Force (ADF) to improve the performance of their radars. It is also developing alternatives to GPS systems to help military personnel, weapons and other items in the field know where they are and where they are going.

“As a defence force, not knowing where your assets are represents a real vulnerability and danger to people in the field. GPS technology is very easily defeated and the risk is soldiers think they’re somewhere where they’re not,” says Luiten.

“We’re working on technologies that can overcome that vulnerability, by providing a sovereign, satellite-based position navigation and timing network or by building terrestrial systems that don’t rely on satellites,” he says.

QuantX Labs’ 40-strong team is growing fast. Luiten says the business is profitable and has never relied on external investment. A strong innovation system in Australia needs to be sustainable and that means it’s very important for businesses like QuantX Labs to earn a return

“Grants are good for solving a problem, but you can’t build a business around that and we can’t build an innovation sector that way either,” he says.

QuantX Labs has grown organically, with support from prime contractors such as BAE Systems.

“They have helped us ensure our systems are compliant with the ADF’s needs, which is always a challenge for a small company. Their engagement with us has been done in a very careful way, to ensure their compliance requirements do not overwhelm us and there is real cultural alignment,” says Luiten.

Finding a champion is always a challenge when it comes to rolling out any innovation. QuantX Labs is solving this problem in novels ways.

“You need somebody who can understand the full pipeline of product development, all the way from blue sky to its application, who can speak with authority and credibility to all the people along that pipeline,” says Luiten.

“The key is to find proponents who can understand the opportunity for your new technology, where it fits in defence and how it can make a difference. They also need to understand the end user’s requirements. We’re solving that problem as a company by partnering with prime contractors.”

QuantX Labs has established a 500-square-metre hub in Adelaide called RavensNest, which is a shared space where project partners come together for purposeful collaboration. The stakeholders who are able to make use of the space include different parties along the defence supply chain including innovators, representatives from defence forces and universities.

“This is not a co-working space. This is cooperating. We involve many partners in our projects, in an agile innovation cycle. This means we’re focused on what’s actually required and we’re not doing things for the sake of it,” says Luiten.

<subhead> Learning from overseas models

DefendTex CEO Travis Reddy says Australia has much to learn from the UK’s approach to defence innovation. The business develops rocket-propelled grenades, body armour and drones as well as other classified devices. It has offices in the US and UK and works with the Canadian, Japanese and New Zealand defence forces.

Reddy says there are many barriers to overcome when it comes to embedding innovation across defence.

“Innovation isn’t in the thing that you do. It is a mindset and it’s a culture. But if I

innovate today and deliver in 10 years’ time, the question is whether what’s delivered will still be innovative. This is the pace of change problem.”

Reddy points to a common problem faced by many pre-revenue companies known as the

valley of death. This is the point in time when the business is developing its technology but has no income.

“Any innovation has a valley of death problem, but in the defence sector, it is a very big one,” he says.

This is due to the long lead times between product development and deployment, due to the nature of defence activities. Defence procurement is also risk averse and it’s common in the military to assess how other allied forces have implemented a new technology before adoption.

“The military is like a game of chess and the people in defence know how to play that game. It’s our job in industry to create a brand new chess piece. But you don’t go to a chess master and ask them what new chess piece they wants, because their mind doesn’t work that way. They know how to use what they’ve got and they don’t know what they need,” says Reddy.

He notes although DefendTex was awarded 18 Defence Innovation Hub projects, none have been deployed by the ADF, yet almost all have been deployed by the US and UK.

This is a sobering state-of-play for local defence start-ups and Reddy wants better links between the innovation ecosystem and defence procurement. The ADF’s new $3.4 billion Advanced Strategic Capabilities Accelerator (ASCA) is one step towards this goal.

ASCA is akin to the US’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, although ASCA is an accelerator not a research agency. ASCA, which supersedes the former Defence Innovation Hub, has recently closed its call for white papers across its priority areas of information warfare and quantum technologies.

“With ASCA, the idea is for defence to indicate what their requirements are and then industry builds it. It addresses the value of death problem, but it cuts off that open call for innovation. So, now defence only gets what it asks for, so you end up with faster horses, rather than inventing the car,” says Reddy.

He laments the loss of the open call for solutions that was part of the former Defence Innovation Hub and says Australia could benefit from the revamped approach the UK now uses to procure for its defence force.

For instance, the UK will now deploy a new technology when its capabilities are only at 60 per cent to 80 per cent of its full potential and make improvements later, known as the spiral development process. But it seems doubtful a similar model would be adopted here.

Although emerging defence businesses may wish the local innovation ecosystem better supported their efforts, it’s likely they will need to live with the existing system for some time to come.

So expect defence start-ups to continue to work with overseas defence forces before their innovations come home.

https://collaborate.partica.online/collaborate/vol-1-ed-1-2024/flipbook/1/