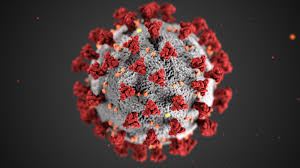

While it’s a collegiate environment, there’s competition among researchers at The Garvan Institute to come up with COVID-19 treatments. Right now, the main game is developing a perfect antibody that can be produced in limitless quantities as a drug to treat the virus.

Garvan’s executive director, Professor Chris Goodnow, who is a globally recognised immunologist, is leading a coordinated COVID-19 research effort in collaboration with research institutes and hospitals across Australia.

“When COVID-19 emerged in January, the institute practically in its entirety started looking very closely at it, on top of their ongoing research in immune diseases, cancer, genomics and epigenetics, and diseases of ageing. Our researchers mobilised themselves to look at what we have that’s unique we can pitch in for what is a war effort. The expertise we have can fill some of the crucial gaps that we have in explaining, preventing and treating COVID-19,” Goodnow says.

Researcher Professor Daniel Christ, a world authority on human antibodies, is an example. His lab, which had been working on a variety of other auto immune diseases, is now working full time on developing a highly-specific, targeted drug to prevent people from being infected or to treat them when they are infected, so they don’t progress to severe disease. The drug may be a stop-gap until a vaccine is found.

“We hope there will be a successful vaccine in due course, which can be given to everyone and which will allow your body to make antibodies that give you immunity to infection. But there’s lots of potential bumps in the road to a vaccine,” Goodnow says.

One is the variability from person to person in how we respond to the virus. “At this stage it’s clear some people make lots of antibodies and others make very few,” he explains. The second bump in the road for a successful vaccine is how long the body will keep making antibodies before a booster is required.

So far, Christ has used antibody gene technology to produce a series of eight human COVID-19 antibodies. “The one that’s furthest advanced as of last week binds the virus with very high affinity, but neutralises its infectivity in tissue culture,” says Goodnow.

The next step is to scale up production of the antibodies to show they are safe and protect against infection in preclinical animal models. Researchers are hoping to begin human testing by the end of the year. Christ and his team is aiming to show the antibodies are safe and effective.

Says Goodnow: “It would be as if you had a great vaccine. People who had been treated would instantly have protective antibodies in their blood stream that would neutralise the virus.”

The treatment is not the same as a vaccine and wouldn’t be given to everyone, but he says it would take the sting out of the tail of the COVID-19 crisis. People who are high-risk such as health workers would need get the antibody drug once every month or so as a top-up by intravenous infusion in a hospital setting.

A similar approach is already taken with premature babies, who receive a human antibody as a drug against respiratory syncytial virus, a common and sometimes severe infection in babies whose immunity is undeveloped. The technique has also been used to treat people with symptoms of the Ebola virus and successfully reduces mortality by between 50 per cent and 70 per cent.

Goodnow says the difficulty in acquiring immunity to coronaviruses is they have a very big genome, much bigger than influenza or HIV/AIDS. “They’ve got lots of tricks up their sleeves science doesn’t fully understand. We don’t tend to produce very strong and large quantities of antibodies that neutralise the virus for very long. We learned from SARS, a close cousin of SARS-CoV-2, that even if people have neutralising antibodies, they are almost undetectable within two years.” In contrast, we have antibodies for decades after receiving a measles or smallpox vaccine.

Aside from trying to understand why we don’t have coronavirus antibodies for longer, the Garvan is also trying to figure out why COVID-19 is so destructive in some people while others are asymptomatic. Working with colleagues around the world, much of its research uses DNA information to explain why the immune system responds differently from one person to the next.

Overall, the institute is approaching COVID-19 from many different angles and all this effort contributes to understanding the body’s reaction to the virus and what can be done to prevent and reduce its harm. It’s noble work, for which we should be grateful is happening right here in Australia.